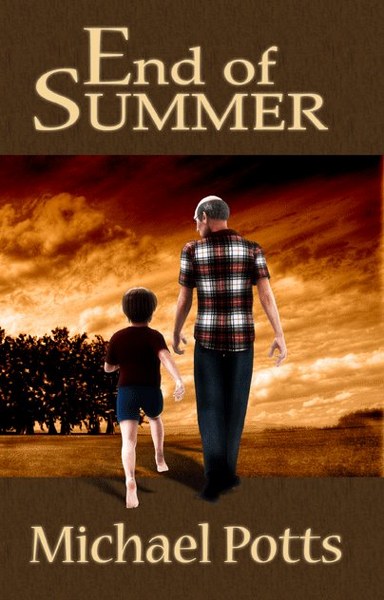

End

of Summer

by

Michael Potts

Genre:

Coming of Age

A

young boy. An old man. And a journey of the heart.

A

middle aged man, Jeffrey Conley, has obsessive interests, including a

fascination with death and the process of dying and a fetish for the

sound of a woman's heartbeat. His wife, Lisa, encourages him to get

help. His psychologist diagnoses him as having Asperger's Syndrome, a

mild condition on the Autism spectrum. When his granny dies, Jeffrey

returns to Tennessee for her funeral, and then walks the same field

he walked with his granddaddy as a child. On that cold, late November

day, Jeffrey walks toward The Thicket, an outcropping of trees and

vines from the woods adjoining the field that crossed the fence and

are invading the field. In that special place he and Granddaddy would

sit and talk as Jeffrey swung on vines or sipped cola. The middle

aged Jeffrey looks back to that time, to the summer of his ninth

year, an idyllic year and a terrible year, a year of joy, a year of

loss and grief. Will Jeffrey Conley be able to discover and

understand his struggles by this journey back into his past. While

remembering Sunday dinners with relatives, hunting rabbits with his

granddaddy, or visiting the town square, Jeffrey rediscovers pain and

the worst loss of his life. Will he be able to make sense of his

life, his past, his obsessions, his faith? Or will he sink into

despair, The Thicket becoming a place of pain rather than redemption?

That is the fundamental problem of the book.

Michael

Potts has taught philosophy at Methodist University since 1994. A

native of Smyrna, Tenn., he received a B.A. in Biblical languages

from David Lipscomb University in 1983, a M.Th. from Harding School

of Theology in 1987, a M.A. in religion from Vanderbilt University in

1987, and a Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of Georgia in

1992. He is the author of Aerobics for the Mind: Practical

Exercises in Philosophy that Anybody Can Do(Tullahoma, TN: WordCrafts

Press, 2014) and has co-edited an anthology, Beyond Brain Death:

The Case Against Brain Based Criteria for Human Death, published by

Kluwer Academic Publishers in 2000. He has twenty-five articles in

refereed scholarly journals, nine book chapters, six encyclopedia

articles, nine book reviews, and ten letters, including one published

in the New England Journal of Medicine. He also has over fifty

scholarly presentations, including an invited presentation at The

Vatican in 2005. He has written three novels, End of

Summer (2011), Unpardonable Sin (2014),

and Obedience (2016), all published by WordCrafts Press.

His poetry chapbook, From Field to Thicket, won the 2006 Mary

Belle Campbell Poetry Book Award of the North Carolina Writers’

Network, and his creative nonfiction essay, “Haunted,” won the

Rose Post Creative Nonfiction Contest the same year. He has also

authored Hiding from the Reaper and Other Horror Poems. He

enjoys reading, creative writing, vegetable gardening, and canning.

Potts, his wife, Karen, and their eight cats live in Coats, N.C.

GUEST POST

Folklore

and Horror

Michael

Potts

Much,

perhaps most, of horror fiction has some relation to folklore.

Ghosts, vampires, werewolves, and zombies were all creatures of

folklore before they found their way into horror fiction. Bram Stoker

read studied legends concerning Vlad Tepes Dracula before writing his

landmark novel. Although H. P. Lovecraft’s “old ones” arose

from an attempt to create a mythology, Lovecraft was interested in

folklore, especially the folklore of his native New England.

Despite

our living in an advanced technological society, folklore still

thrives, and not only in the sense of “urban legends.” Stories of

ghosts and hauntings continue to be a part of American folklore, and

provide fuel for groups of paranormal investigators (I am a member of

one such group myself). The story of the Bell Witch of Robertson

County, Tennessee is a well-known part of Tennessee folklore. Since I

am originally from Tennessee and am familiar with the legend, it

serves as a good starting point for my discussion of folklore and

horror.

Most

of you are probably familiar with the story of the Bell Witch, but

here is a short synopsis for those who are not. John Bell, a farmer

in Robertson County, Tennessee, was haunted by a spirit during the

second decade of the nineteenth century.i

The phenomena described included strange animals that disappeared,

poltergeist phenomena, and a disembodied voice that tormented John

Bell. Supposedly the spirit poisoned him to death in 1820. There is

some speculation, fueled by the Brent Monahan’s novel, An

American Haunting: The Bell Witch Story,

ii

and the movie based on it, that John Bell’s daughter, Betsy, may

have been responsible for the haunting because her father violated

her sexually.

Now

what is most frightening about folklore stories such as the Bell

Witch as opposed to horror fiction is the question, “Is there truth

behind this legend? If so, how much? And if the accounts of the Bell

Witch are true, could something like this happen again?” Horror

fiction carries with it the paradox that we are afraid of something

that does not exist.iii

Folklore opens the possibility that we are afraid of something that

may have existed and may still exist.

Part

of what adds to the air of reality about folklore is that the events

described in the stories are said to have occurred in actual places.

I have visited the farm formerly owned by the Bell family and have

been on a tour of the “Bell Witch Cave” on the property. John

Bell and the other persons in the legend were real people, and one

can view their tombstones today. Those people interested in the

Dracula legend can visit some of the places in Rumania Vlad Tepes

Dracula once lived and roamed. Someone interested in Lovecraft’s

stories can focus on the folklore he studied and visit the places

that remain that are part of this folklore.

John

Gardner says that “In any piece of fiction, the writer’s first

job is to convince the reader that the events he recounts really

happened, or to persuade the reader that they might have happened

(given small changes in the laws of the universe)…”iv

The horror writer can make use of folklore to lend an illusion of

reality to a story. The more detailed the research into people and

places, the better—but the author must work such details into the

story in a skillful way, and omit or change details that are not

needed for plot or characterization. But the skillful use of folklore

in a horror story that results in strong verisimilitude can draw the

reader into “the vivid and continuous dream”v

of a story in an effective way. It can move a reader to ask, “Could

something like this really happen? Did something like this really

happen. Maybe it’s happening now.”

iThe

best sources for the Bell Witch legend are M. V. Ingram, An

Authenticated History of the

Famous

Bell Witch

(Nashville: Rare Book Reprints, 1961 [1894]) and Charles Bailey

Bell, A

Mysterious

Spirit: The Bell Witch of Tennessee

(Nashville: Charles Elder, Bookseller, 1972

[1934]).

iiBrent

Monahan, An

American Haunting: The Bell Witch,

2nd

ed. (New York: St. Martins

Griffin,

2006).

iiiNoël

Carroll, The

Philosophy of Horror, or Paradoxes of the Heart

(New York and London:

Routledge,

1990), 59.

ivJohn

Gardner, The

Art of Fiction

(New York: Vintage Books, 1983), 22.

Follow

the tour HERE

for exclusive excerpts, guest posts and a giveaway!

No comments:

Post a Comment